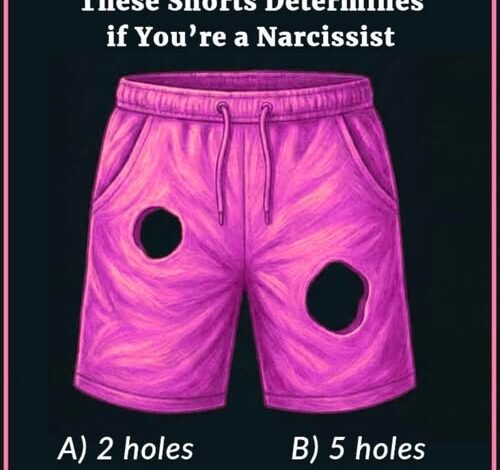

What the Popular Shorts Trend on Social Media Is Really Revealing!

At first glance, the image looks trivial: a battered pair of shorts laid out flat, fabric frayed, seams worn, a few obvious tears visible at a glance. On its own, it would barely register as content worth stopping for. But paired with a provocative caption—“How many holes you see determines if you’re a narcissist”—the image transforms instantly into something far more powerful. It becomes a test, a challenge, and a subtle psychological hook that invites viewers to judge themselves and others in seconds.

That framing is precisely why the image spreads so fast.

The puzzle doesn’t promise entertainment alone. It promises insight. It implies that your answer reveals something hidden about who you are, nudging curiosity and ego at the same time. People don’t just want to solve it—they want to know what their answer says about them. And once they answer, they feel compelled to explain, defend, or argue it. The result is exactly what social platforms reward most: engagement, debate, and emotional investment.

Despite the dramatic language, the image is not a diagnostic tool. It does not identify narcissists, personality traits, or psychological profiles. Its real function is far simpler and more interesting. It exposes how quickly people make assumptions, how differently individuals process visual information, and how strongly they cling to their first interpretation once they’ve committed to it.

Most viewers respond almost instantly. They look at the shorts, notice the two obvious tears in the fabric, and answer “two” without hesitation. This reaction reflects fast, intuitive thinking. The brain prioritizes what stands out most clearly and delivers a conclusion with minimal effort. In everyday life, this kind of thinking is efficient and often useful. It allows people to navigate the world quickly without overanalyzing every detail.

But once someone posts “two,” the comment section begins to shift.

Others point out something the first group overlooked: the shorts already have holes by design. Two leg openings. One waist opening. When those are added to the two visible tears, the total becomes five. This answer feels more complete to many people, and those who arrive at it often do so with a sense of correction or superiority, as if they’ve uncovered a hidden layer others missed.

From there, the interpretations keep multiplying.

Some viewers argue that each tear creates two holes—one on the front and one on the back—because light can pass through both layers of fabric. Others examine seams, overlaps, and structural details, pushing the count to seven, eight, or even nine. At this stage, the puzzle stops being about the shorts and becomes about reasoning itself. People are no longer just answering; they are constructing arguments.

This is where the illusion of psychological insight comes in.

The caption’s reference to narcissism gives people a narrative to attach to their reasoning. Those who answered quickly may feel defensive, interpreting criticism as a personal attack. Those who counted more holes may feel validated, interpreting complexity as intelligence or depth. The label doesn’t diagnose anything—it simply polarizes responses and encourages people to take sides.

What the image actually reveals has nothing to do with narcissism. It highlights differences in cognitive style.

Some people rely on instinctive perception. They answer quickly, trust their gut, and move on. Others engage in structural thinking, stepping back to consider function and design. Still others default to layered analysis, examining edge cases and redefining terms to expand the solution space. None of these approaches are better or worse. They are simply different ways of processing information.

The reason the debate becomes heated is not because people care deeply about shorts. It’s because once someone publicly commits to an answer, that answer becomes tied to identity. Being “wrong” starts to feel like being exposed, especially when the framing implies a character flaw. So people double down. They argue definitions. They accuse others of overthinking or underthinking. They defend logic not to be correct, but to be consistent with who they believe themselves to be.

Social media thrives on this dynamic.

Short-form platforms reward speed, certainty, and confidence. The image fits perfectly into that ecosystem. It looks simple enough to answer instantly, but ambiguous enough to sustain endless debate. It invites users to comment quickly, then return repeatedly to defend their position. Each interaction feeds the algorithm, pushing the image further into circulation.

There is also a deeper cultural element at play. In a digital environment flooded with tests, quizzes, and “what this says about you” content, people have been trained to see puzzles as mirrors of personality. Whether it’s optical illusions, color perception tests, or logic riddles, the promise is always the same: your answer reveals who you really are. Even when viewers consciously know this isn’t true, the framing still works on an emotional level.

The shorts image is effective because it feels personal without being personal. It doesn’t ask about beliefs, values, or experiences. It asks about what you see. That makes it feel objective and safe, even as it subtly invites judgment.

What’s most revealing is not which number someone chooses, but how they react when challenged. Some people shrug and move on. Others feel compelled to prove their reasoning. Some mock alternative answers. Some rewrite the rules entirely. These reactions say far more about human behavior than any hole count ever could.

In the end, the image succeeds because it turns perception into performance. It transforms a simple visual into a social signal. People aren’t just counting holes—they’re signaling intelligence, awareness, logic, or intuition to an invisible audience. And once that signal is sent, it becomes something to protect.

The irony is that the most accurate interpretation is also the least interesting to argue about: there is no single correct answer. The number of holes depends entirely on how one defines a “hole,” what assumptions are made about fabric layers, and whether design features count. The puzzle is deliberately underspecified, which is exactly why it works.

What this trend really reveals is not narcissism, but how easily people are drawn into defending conclusions that were formed in seconds. It shows how quickly curiosity turns into certainty, and certainty into conflict. And it demonstrates how a simple image, paired with a loaded caption, can expose the mechanics of attention, identity, and debate in the digital age.

The shorts are just the bait. The real subject is how we see—and how fiercely we insist that our way of seeing is the right one.