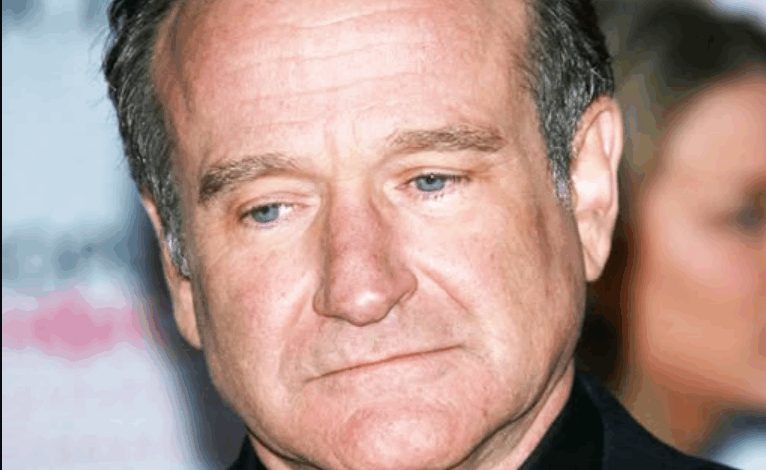

Robin Williams Final On-Screen Line Continues to Break Hearts!

Robin Williams’ death in 2014 hit the world like a punch to the gut. For decades, he’d been the electric force behind some of the most memorable films ever made — Good Will Hunting, Dead Poets Society, Mrs. Doubtfire, Aladdin, the list goes on. He had that rare spark, the kind that felt endless and effortless. On screen, he was unstoppable. Off screen, he was warm, deeply thoughtful, and painfully human. So when news broke in August 2014 that he had taken his own life, it felt impossible. How could someone so full of light reach a place that dark?

At first, people speculated — depression, addiction, burnout. The usual explanations tossed around when the public tries to make sense of tragedy. But the truth turned out to be far more complex, and far more devastating. After his autopsy, doctors discovered that he had been battling severe Lewy body dementia — an aggressive, destructive neurological disease that he never knew he had. His wife, Susan Schneider Williams, later shared what the doctors told her: his brain was full of Lewy bodies. Every region was being impacted.

She said she didn’t even know what Lewy bodies were until they explained it, but once she understood, everything clicked. The confusion. The anxiety. The strange cognitive symptoms. The fear he couldn’t articulate. “The fact that something had infiltrated every part of my husband’s brain? That made perfect sense,” she said in an interview years later.

Lewy body dementia is brutal. The National Institute on Aging describes it as a condition that affects thinking, movement, mood, and behavior — and it progresses fast. Dr. Bruce Miller, a leading neurologist at UCSF, said Williams’ case was one of the most aggressive he had ever seen. He even admitted he was amazed that the actor had managed to function at all. The man who had lifted millions with his humor was quietly fighting a war inside his own brain.

In the HBO documentary Come Inside My Mind, there’s a moment that now feels chillingly prophetic. An old interview clip shows Robin being asked about his fears. He answers honestly: “I guess I fear my consciousness becoming, not just dull, but a rock. I couldn’t spark.” That line hits hard now. His internal spark — the quick wit, the mental fireworks — was exactly what the disease was attacking. And he felt it happening.

Susan later said Robin used to tell her, “I just want to reboot my brain.” He knew something was wrong. He just had no idea how bad it was. She promised him they’d get to the bottom of it, not knowing the truth would only come after his death.

For fans, one detail that continues to echo is his final onscreen line. Many assumed his last film moment was as Teddy Roosevelt in Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb, where he delivers the gentle, uplifting line: “Smile, my boy. It’s sunrise.” Given the circumstances, the line feels poetic, almost like a farewell. But that wasn’t actually his last piece of dialogue.

His final live-action performance came in the film Boulevard, released after his death. His last line there is far more haunting — and far more revealing in hindsight. As reported by Parade, fans have called the words “hauntingly beautiful,” because they seem to unintentionally mirror the way his life ended.

The line was simple: “I drove down a street one night. A street I didn’t know. It’s the way your life goes sometimes. I’ll drive down this one and another. And now, another.”

Looking at it now, it feels like a man reflecting on paths, choices, and the places life forces you to go. It feels heavy — maybe too heavy — because once you know the truth about his illness, those words sound like someone who had been navigating unfamiliar mental territory for far too long.

In interviews after his death, Susan Schneider Williams has worked relentlessly to bring awareness to Lewy body dementia. She’s spoken about how misunderstood it is, how often it gets misdiagnosed, and how families feel helpless watching their loved one change in ways they can’t explain. She said she wished the world understood that Robin wasn’t himself, not because he didn’t love life anymore, but because the disease took away the part of him that made life liveable.

Lewy body dementia doesn’t just attack memory — it scrambles perception, disrupts thinking, and creates terrifying hallucinations. It strips away the ability to reason or trust your own mind. It is one of the cruelest neurological disorders there is. And Robin Williams had one of the worst cases doctors had ever seen.

But Robin Williams wasn’t the disease. He wasn’t the tragedy. He wasn’t the heartbreaking ending. He was the joy he created. He was the unreal talent, the relentless kindness, the spark that lit up every room he walked into. He was the reason millions of people felt less alone. He was the voice that comforted children, the performer who could improvise entire scenes in one breath, the man who gave everything he had to make other people feel something.

His work lives on because it came from a place of authenticity — a rare thing in entertainment. He didn’t perform to impress; he performed to connect. And that connection still holds.

Fans still talk about him like he’s a friend they lost too soon. Clips of his interviews still make the rounds online. His best scenes still get shared by people who need a laugh or a lift. His legacy is not tragedy — it’s impact.

And even though his last onscreen words weren’t intended as a message, they feel like one. Life is a series of streets we don’t always recognize, paths we didn’t expect to take. Some bright. Some dark. Some we choose. Some we never would have chosen. But we move forward anyway, one street after another.

If you or someone you know is struggling, help exists. Call or text 988. Someone will answer. Someone will listen.

Robin Williams may be walking down a different street now, but the world hasn’t forgotten him — not the man, not the art, not the heart.

He made people feel. That’s the kind of immortality most artists only dream of.