My Daughter Said Something To A Crying Biker That Completely Wrecked Me

I watched my daughter walk up to a crying biker in the park and say something that completely wrecked me. She’s five years old. She doesn’t know what she did. But I’ll never forget it.

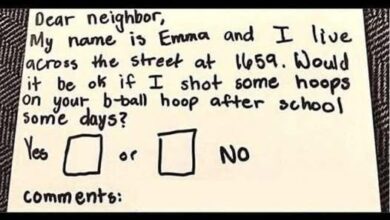

We were at Riverside Park on a Saturday morning. Emma was on the swings. I was on a bench checking my phone like every other distracted parent.

That’s when I noticed him.

A man sitting alone on the bench across the playground. Big guy. Leather vest. Tattoos up both arms. Bandana. Boots. Full biker.

He was hunched forward with his elbows on his knees. His shoulders were shaking.

He was crying.

Not quiet tears. Deep, broken sobs. The kind that come from somewhere you can’t reach.

Other parents noticed too. A mom pulled her kid closer. A dad steered his son toward the other end of the playground. People moved away from him like grief was contagious.

I’ll be honest. My first instinct was to grab Emma and leave. Not because I thought he was dangerous. But because I didn’t know what to do with a grown man falling apart in public. It made me uncomfortable.

Emma didn’t get that memo.

She jumped off the swing and walked straight toward him. No hesitation. No fear. Just a five-year-old girl in a princess dress walking toward a 250-pound biker who was sobbing on a park bench.

“Emma,” I called. “Come back here.”

She didn’t listen.

I stood up. Started walking after her. But she was already there.

She stopped right in front of him. He didn’t see her at first. His head was down. His hands were covering his face.

Emma reached up and touched his knee.

He looked up. His face was red and wet. His eyes were swollen.

My daughter looked at this man. This stranger. This person every other parent in the park had avoided.

And she said six words that stopped my heart.

“I don’t like being sad alone.”

The biker stared at her. His mouth opened but nothing came out.

Emma climbed up onto the bench next to him. Sat down. Folded her hands in her lap like she was settling in for a long stay.

“My name is Emma,” she said. “I’m five. What’s your name?”

The biker looked at me. I was frozen about ten feet away. Not sure if I should grab her or let this play out.

“Hank,” he said. His voice was raw. Shredded.

“Hi Hank. Why are you crying?”

“I’m… I lost somebody.”

“Like lost lost? Or heaven lost?”

He closed his eyes. “Heaven lost.”

Emma nodded. Very serious. Very matter-of-fact.

“My goldfish went to heaven. His name was Captain Bubbles. I was really sad. Daddy said it’s okay to be sad when you miss somebody.”

Hank looked at her. This tiny girl in a purple dress with glitter shoes and tangled hair. Talking to him about a goldfish like it was the most important thing in the world.

“Your daddy’s right,” Hank said.

“Do you want me to sit with you for a while? When I’m sad, I don’t like sitting by myself. It makes the sad bigger.”

“It makes the sad bigger,” Hank repeated. Like he was hearing something he’d always known but never had words for.

“Yeah. But if somebody sits with you, it makes the sad smaller. Not all the way gone. But smaller.”

I watched a 250-pound biker with a skull tattoo on his neck start crying harder because a five-year-old girl explained grief better than any therapist could.

I walked over slowly. Sat down on Emma’s other side.

“I’m sorry,” I said to Hank. “She just goes where she wants. I can take her—”

“Don’t,” he said. “Please. She’s fine.”

Emma patted his arm. “See, Daddy? He needs a friend.”

I didn’t know what to say. So I just sat there. The three of us on a park bench in the morning sun.

After a few minutes, Emma got bored with sitting still. She’s five. That’s what happens. She asked if she could go back to the swings.

“Go ahead, baby,” I said.

She hopped down. Looked at Hank. “I’ll be right over there if you need me, okay?”

He nodded. “Okay, Emma. Thank you.”

She ran off. Back to the swings. Back to being five.

Hank and I sat in silence for a while. I should have left. Should have minded my own business. But something kept me on that bench.

“You don’t have to stay,” Hank said.

“I know.”

“Most people crossed the street when they saw me crying. Like I was going to hurt someone.”

“People don’t know what to do with pain that isn’t theirs.”

“Your daughter does.”

That hit me. Because he was right.

“She’s always been like that,” I said. “Even as a baby. She’d cry if other kids cried. Like she could feel it.”

Hank wiped his face with his hands. Big hands. Scarred knuckles. Working hands.

“Can I ask who you lost?” I said.

He was quiet for a long time. I thought he wasn’t going to answer.

“My daughter,” he said. “Lily.”

My stomach dropped.

“She died when she was five.”

The same age as Emma. The same age as the girl who’d just sat next to him and held his arm.

“Twenty-two years ago today,” Hank said. “I come here every year. This was her park. She loved those swings.”

He pointed to where Emma was swinging. The exact same swings.

“She used to beg me to push her higher. ‘Higher, Daddy. Higher.’ She wasn’t scared of anything.”

“What happened?” I asked. Then caught myself. “I’m sorry. You don’t have to—”

“Car accident. My wife was driving. Truck ran a red light. Hit the passenger side where Lily was sitting. She died at the hospital. My wife survived but she never forgave herself.”

He said it flat. Like he’d told it so many times the words had worn smooth. But his eyes told a different story.

“I’m so sorry,” I said.

“We divorced two years later. Couldn’t look at each other without seeing her. Without blaming each other. Without wondering what we could have done different.”

“There was nothing you could have done.”

“I know. Took me fifteen years of therapy to believe that. But knowing it up here,” he tapped his head, “and knowing it in here,” he tapped his chest, “are two different things.”

Hank leaned back on the bench. Watched Emma on the swings.

“She looks like Lily,” he said. “Same hair. Same fearlessness. Same way of walking up to people like they already belong to her.”

I looked at Emma. Pumping her legs. Going higher. Laughing.

“Lily used to do that thing your daughter did,” Hank said. “Walk up to strangers who were upset. She had no filter. No walls. She just went to where the pain was and sat down.”

“Kids don’t know they’re supposed to be afraid of feelings.”

“We teach them that. They don’t start that way.”

He was right. Somewhere between five and thirty-five, I’d learned to look away from people in pain. To give them “space.” To mind my own business.

My five-year-old daughter hadn’t learned that yet. And she’d done in thirty seconds what I couldn’t have done in a lifetime.

“That thing she said,” Hank continued. “About not liking being sad alone.”

“Yeah.”

“Lily said almost the exact same thing to me once. I came home from work one day. Bad day. I was sitting in the kitchen with my head in my hands. Lily climbed up on my lap and said, ‘Daddy, you don’t have to be sad by yourself. I’m right here.’”

His voice broke.

“She was four. Four years old. And she knew exactly what to say.”

I felt something crack in my chest. Not break. Crack. Like a wall I didn’t know was there.

“When your daughter walked up to me today… in her little dress… and touched my knee…” Hank shook his head. “For a second. Just one second. I felt like Lily was here. Like she sent someone to tell me it’s okay.”

“Maybe she did.”

“I don’t believe in that stuff. Ghosts and spirits and messages from beyond. But I’ll tell you what. That little girl knew exactly what I needed to hear. And she said it without anyone teaching her.”

I watched Emma play while Hank talked. He told me about Lily. About how she loved butterflies and refused to eat anything green. About how she called motorcycles “Daddy’s thunder horse.” About how she’d fall asleep on his chest while he watched TV and he’d stay perfectly still for hours so he wouldn’t wake her.

He told me about the years after she died. The drinking. The rage. The fights. The nights he thought about not being here anymore.

“The club saved me,” he said. “My brothers. They didn’t let me disappear. Showed up at my door every day. Dragged me out. Made me ride. Made me eat. Made me live when I didn’t want to.”

“That’s real brotherhood.”

“It’s the only reason I’m still here. Them and this park. I come here every year on her birthday. Sit on this bench. Talk to her. Tell her what’s happened. Tell her I miss her.”

“Every year for twenty-two years?”

“Every year. Rain or shine. Sometimes I stay for an hour. Sometimes I stay all day. The park people know me. They don’t bother me anymore.”

He looked at his hands. “But this is the first year anyone’s sat with me. In twenty-two years of coming here, nobody’s ever come over. Not once.”

“Until Emma.”

“Until Emma.”

He smiled. First time I’d seen him smile. It changed his whole face. Made him look younger. Softer.

“She’s special,” he said. “You know that, right? Not every kid walks toward the scary crying biker in the park.”

“She doesn’t see scary. She just sees sad.”

“Hold onto that. Protect that. Don’t let the world teach it out of her.”

We sat there for another hour. Talking. Watching Emma play. She’d come back every few minutes to check on Hank.

“You doing okay, Hank?” she’d ask, hands on her hips.

“I’m doing better, Emma. Thank you.”

“Good. I’m going on the slide now.”

“Have fun.”

Then she’d run off again. Our tiny emotional paramedic making her rounds.

Around noon, Hank stood up. Stretched his back.

“I should go,” he said. “Thank you. For staying. For letting your daughter be who she is.”

“Thank you for talking to me. For telling me about Lily.”

He reached into his vest pocket. Pulled out a small laminated photo. A little girl with dark hair and a huge smile. Sitting on a bench. This bench.

“That’s my Lily,” he said.

I looked at the photo. She had the same fearless expression Emma had. The same bright eyes. The same energy that said I’m going to walk right up to you and change your day.

“She’s beautiful,” I said.

“She was.”

He put the photo back. Then he looked at me with an expression I’ll never forget. Not sad anymore. Something deeper. Grateful.

“Can I give your daughter something?” he asked.

“Sure.”

He walked over to Emma. Crouched down. She stopped playing and looked at him.

“Emma, I want to give you something.”

He pulled a small metal pin from his vest. A butterfly. Silver and blue.

“This was my daughter’s favorite thing,” he said. “Butterflies. She loved them. I’ve carried this pin for twenty-two years. I want you to have it.”

Emma’s eyes went wide. “It’s so pretty.”

“It is. And so are you. Thank you for sitting with me today.”

“You’re welcome. Are you still sad?”

“A little. But the good kind of sad. The kind that means you loved somebody very much.”

Emma thought about that. “Captain Bubbles sad.”

Hank laughed. Actually laughed. “Yeah. Captain Bubbles sad.”

She hugged him. Arms around his neck. No hesitation. He closed his eyes and hugged her back. Carefully. Like she was made of glass.

I almost lost it right there.

When they pulled apart, Emma held up the pin. “I’m going to keep this forever.”

“You do that.”

Hank stood up. Looked at me. Extended his hand.

I didn’t shake it. I hugged him. I’m not a hugger. I don’t hug strangers. But I hugged this man and he hugged me back and for a moment we were just two fathers standing in a park where his daughter used to play and mine still does.

“Take care of her,” Hank said in my ear. “Every second counts. You hear me? Every single second.”

“I hear you.”

He walked to his motorcycle. A beat-up Harley parked on the street. Put on his helmet. Started the engine.

Emma waved. He waved back.

Then he rode away.

I sat back down on the bench. Emma climbed up next to me.

“Daddy, can we stay longer?”

“Yeah, baby. We can stay as long as you want.”

She leaned against me. “Hank was really sad. But I think he’s a little better now.”

“I think so too.”

“His daughter is in heaven with Captain Bubbles.”

“Maybe so.”

“I bet she’s pushing Captain Bubbles on a swing.”

I pulled her close. Kissed the top of her head. Breathed her in. Shampoo and playground dirt and the strawberry jam she’d had for breakfast.

“Daddy, why are you squeezing me so hard?”

“Because I love you.”

“I know that, silly. You don’t have to squeeze so hard about it.”

I laughed. But I didn’t let go.

That was three months ago. Some things have changed since that morning.

I put my phone away at the park now. Every time. I watch Emma play. I push her on the swings. I catch her at the bottom of the slide. I’m there. Actually there. Not checking emails. Not scrolling. Present.

Because a man named Hank would give everything he has for one more afternoon at the park with his daughter. And I was wasting mine staring at a screen.

Emma wears the butterfly pin on her backpack. She tells everyone about it. “A sad biker gave it to me because I sat with him. His daughter loved butterflies.”

Her teacher called me about it. Thought it was concerning that Emma was talking to strange men in parks. I explained the story. The teacher cried.

I think about Hank a lot. About Lily. About how twenty-two years of grief brought him to that bench every year and not one person in twenty-two years had the courage to sit with him.

Except my daughter. Who didn’t need courage because she hadn’t learned to be afraid yet.

I went back to that park on a Wednesday. Alone. I wanted to see if Hank would be there. He wasn’t. But someone had left flowers by the bench. Fresh ones. Pink and purple. Lily’s favorites, maybe.

I sat there for a while. Thought about what Emma said.

I don’t like being sad alone.

Six words. From a five-year-old. And they wrecked me. Not because they were profound. But because they were true. And because every adult in that park knew it and not one of us acted on it.

We’ve all been trained to walk past the crying stranger. To look away. To give space. To protect ourselves from the discomfort of someone else’s pain.

My daughter hasn’t learned that yet.

And I pray she never does.

Emma taught me something that morning. Something I should have known. Something Hank’s daughter Lily knew. Something every five-year-old knows before the world teaches them otherwise.

Sad people don’t need space.

They need someone to sit down and say I’m here.

That’s it. That’s the whole secret.

I’m here.

Hank, if you ever read this, thank you. For telling me about Lily. For the butterfly pin. For reminding me what matters.

And thank you for not leaving that bench before Emma got there.

She needed to meet you too. She just doesn’t know it yet.