My DIL Humiliated a 13-Year-Old at Her Party… Then I Pulled Out Two Plane Tickets

Laurel’s birthday fell on one of those clear December nights that feel like glass—pretty until you touch them and cut yourself. She’d booked the back room at a trendy bistro where the candles were real and the flowers fake, and everyone had practiced smiles they kept polishing with sips of prosecco.

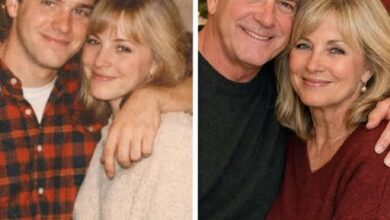

My son, Dan, looked tired but proud, the way he always did when he believed he was keeping the peace. Beside me, Mary tugged the hem of her navy dress, the one she’d chosen because it “felt grown-up without trying too hard.” She is thirteen and careful like that.

Her gift sat on her lap, a white box tied with red gingham ribbon. Inside was the shawl she’d saved for all autumn—babysitting money from Friday nights, dog-walking for our neighbor who always added a dollar and a peppermint. She’d found the shawl at the holiday craft market, run her fingers over the soft fringe, and told the vendor, “It’s for my new stepmom.” The woman had smiled. “It looks like patience,” she’d said. “Whoever it’s for should know it took time.”

Laurel made an entrance late, of course, a coat over her shoulders the way actresses wear them in magazines, clutch bag hugged to her ribs like a secret. She air-kissed Dan, air-kissed half the room, and took her seat at the head of the table like she’d been born there. “Shall we open presents?” she trilled, and by “we” she meant “me.”

Paper fluttered like doves. Candles flickered. She held earrings to her ears and angled her face to catch the sparkle. She cooed over a designer scarf, squealed at a gift card tucked into a glittery envelope. She was gracious in the way people are when they suspect a camera’s on them.

Then she reached for Mary’s box.

Mary sat taller. I felt her inhale, the same way I used to feel her mother inhale before blowing out birthday candles—quick, hopeful, like the breath could carry a wish all the way to heaven. Laurel tugged the ribbon loose and lifted the lid. Tissue whispered. She drew the shawl out the way one draws a curtain.

It was beautiful. A pale, moonlit blue, handwoven with a subtle pattern that shifted when you turned it, fringe that fell in neat little tassels. Even Laurel’s face softened for a half-second.

Then her mouth curled.

“Well, Mary…” She held the fabric between two nails, as if it might stain them. “I’m your new mother now. You could’ve put more effort into my gift. Saved up for something more… valuable.” She let the word dangle. “This is… ugly.”

The room didn’t go quiet so much as it stopped breathing. Forks hovered. Someone’s laugh shriveled in their throat. Mary stayed very still. Her face flushed the way it does when cold wind slaps you—high on the cheekbones. She blinked hard, twice, the way she does when she refuses to let tears fall.

I felt the heat rise from my chest to my mouth like a tide. There are moments in life when you hear a door click from the inside—something closing that you will not open again. This was one of them.

I stood, my napkin sliding off my lap and puddling on the floor. Laurel looked up, surprised, then watchful. She thinks of people as audiences.

“Don’t worry, Laurel,” I said, and my voice carried farther than I expected. “I brought you a very valuable surprise tonight. Something much bigger than a shawl.”

Her eyes lit with a jumpy hunger. She leaned forward. “Oh?” she purred, as if I might pull a diamond from my handbag and fasten it around her throat.

I reached into my purse and took out the envelope I’d put there before I left the house. Dan’s eyes flicked to it, then to me. He had no idea. I handed it to Laurel.

She slid a manicured finger under the flap, drew out the paper with that same perfumed grace. Her smile wavered as she read. “Plane tickets?” she said, and then read again, as if it might change. “To… Hawaii?”

“For me and Mary,” I said. “We leave after New Year’s. Two weeks. Beach, volcanoes, shaved ice. You know—valuable things.”

A few gasps, an “oh!” that tipped into a cough. Someone’s wineglass chimed against a plate. Laurel looked from the tickets to me, to Mary, back to the tickets. She tried to find a joke and didn’t.

“And,” I added, because some truths need scaffolding, “I’ve saved every text you’ve sent about Mary. Every ‘she’s so dramatic,’ every ‘she needs to toughen up,’ every ‘her mother’s ghost needs to get out of this house.’ I have dates, times, screenshots. If I need to stand in front of a judge to protect my granddaughter’s well-being, I will. Cheerfully.”

Dan made a strangled sound. The guests froze like mannequins in a department store window. At my side, Mary’s hand found mine. Her fingers, small and damp, threaded into my palm like a promise.

Laurel recovered the way people do when they’re not used to losing. “This is highly inappropriate,” she said to the table, seeking agreement. “It’s my birthday.”

“It is,” I said. “And on your birthday, you had a chance to be kind to a child. You chose not to. Consider this a candle you didn’t get to blow out.”

We collected our coats. Mary tucked the shawl back into its tissue, then hesitated—looked up at Laurel, and lifted her chin in a gesture that belonged to her mother, not to me. “I’ll take this back,” she said softly. “I know where it’ll be appreciated.”

We left. We walked out under a winter sky full of clean stars and a moon like a clipped thumbnail, our breath making little ghosts in the air. In the car, Mary finally cried, the quiet, careful kind that doesn’t shake the shoulders but empties the eyes. I let her. I drove until the city softened and the roads turned into familiar lines leading home.

Dan came by the next afternoon. He stood in my doorway with his hands shoved into his coat pockets, the way he did as a boy when he’d broken something and needed to confess it. “Mom,” he said, then had to try again. “Mom, I ignored it. I didn’t want to see.”

“I know,” I said. I didn’t tell him I’d been waiting for him to say that for months. “What matters is what you do next.”

He sat at my kitchen table, stared at his knuckles. “I promised her mother I’d protect her,” he said, and his voice went thin. “I promised.” He swore then to put Mary first—not as a slogan, but as a practice. Therapy was the first word we both said without arguing.

Hawaii was a lesson in how laughter sounds when you forget you can make it. We ate fruit that stained our fingers, let salt dry on our skin, and learned the names of birds. Mary wore a hibiscus behind her ear and told a taxi driver she’d never seen water so blue. She let the ocean push and pull at her ankles and decided not to be afraid of the waves. On the last night, we sat on the sand while fire dancers spun circles of light, and Mary leaned her head on my shoulder. “I thought it would hurt forever,” she said. “Maybe it won’t.”

When we came home, Laurel was quieter. There are many languages for silence—guilt, boredom, calculation. Hers was the kind people use when they’ve met a line and don’t want to trip it again. The texts stopped. The “jokes” dried up. She still rearranged the living room like it was a chessboard and sometimes mistook control for care, but when she looked at Mary, she looked longer. The first time she asked Mary how school was and then stayed for the answer, I sat at the window with my tea and pretended not to listen.

One night, a month after our return, the four of us sat at Dan’s table with takeout containers and paper napkins. Mary told a story about the science fair and laughed in the middle of it—really laughed, head back, careless. Laurel startled, then smiled. It was small and genuine and a little lost, the way smiles are when someone is practicing a new skill.

Make no mistake: I keep the envelope in my desk. I keep the screenshots. I keep the promise I made to a woman I loved and to a girl I would cross oceans for. I am not a saint and I will not be silent if the blade of anybody’s words turns toward Mary again.

But I have learned this, too: sometimes the loudest thing you can do is stand up and draw a boundary; sometimes the kindest is to step back and let a child see herself reflected in blue water and blazing fire until her own light comes back.

Laurel knows that there are tickets I will buy, lines I will draw, rooms I will walk out of with Mary’s hand in mine. And Mary knows this: shawls can be taken back, laughter returns, and love—real love—does not require you to earn it with gifts, or silence, or swallowing the hurt until it disappears. It requires you to show up. It requires you to stay.