Professor Dares Janitors Kid to Fix an IMPOSSIBLE Engine, 10 Minutes Later Everyone Is Shocked

The fog lingered low over Pasadena that morning, wrapping the campus in silence as the first hints of daylight touched the brick buildings of Caltech. The engineering hallways were quiet, save for the occasional whir of a coffee machine or the rustle of notebooks behind closed doors. Into this stillness walked a boy who looked as though he didn’t belong. His shoes were worn thin, his coat patched at the elbows, and in his hand was a folded envelope, creased from being held too tightly. Elliot Granger was twelve years old, and he was walking into a world that did not expect him.

He stopped outside room B231, where a plaque read: “Advanced Thermodynamics and Internal Combustion. Professor Margot Richardson.” Elliot smoothed his coat and stepped inside. The lecture hall descended like a bowl, rows of desks sloping toward a massive cutaway engine at the front. Equations, symbols, and diagrams filled the whiteboards. To Elliot, it was more beautiful than any cathedral. But the room froze when Professor Richardson noticed him.

“This class isn’t for janitors’ kids,” she said evenly. “You’re in the wrong building.”

Elliot’s hand trembled as he held out the envelope. “I received a letter from the admissions board. I’m supposed to be here.” A graduate assistant carried the letter to Richardson. She skimmed it, folded it without expression, and said, “Fine. Back row. Don’t interrupt.”

He slipped into the last seat near a vent, pulled out a battered notebook reinforced with tape, and wrote at the top of the page: Thermodynamics is beautiful.

The lecture moved quickly. Richardson spoke about the first law of thermodynamics with the kind of certainty that assumed everyone in the room already knew. Elliot’s pencil never stopped. Around him, whispers rose. “Is that the janitor’s kid? Probably some charity case.” He ignored them. His father, a campus janitor who spent years repairing boilers no one else would touch, had taught him that machines never lied. People could, but steel and pistons always told the truth—if you listened.

At the front of the room stood a test engine, silent, heavy, and flawed. Richardson mentioned it had failed performance tests and would be scrapped. After class, while the others filed out, Elliot lingered. He circled the engine, placing a hand gently on its casing. He leaned close and heard it—the faint rattle of a bearing, the whisper of misalignment. Something was wrong. When Richardson found him, her voice was sharp. “Step away. That machine costs more than your house.” Elliot nodded and backed off, but not before scribbling in his notebook: Rattle in cylinder 2. Possible wear. Check oil path.

The next lectures tested him. When Richardson asked about entropic compression, no one answered. Elliot finally spoke: “Temperature rises. No heat exchange. All the work goes into internal energy.” She paused, then nodded. Correct. Slowly, the room began to shift. Students who mocked him started borrowing his notes. One, Toby, asked to study with him. Even Dylan, the loud skeptic, grew quieter. Elliot never pushed himself forward. He only spoke when the silence demanded an answer.

Three weeks in, Richardson presented a question meant to stump the class: why does the Otto cycle destabilize at high compression ratios? Elliot explained knock in detail—the premature ignition of fuel, shockwaves colliding with chamber walls, and why hemispherical heads reduce the risk. His words silenced the room. Richardson said only one word: “Correct.”

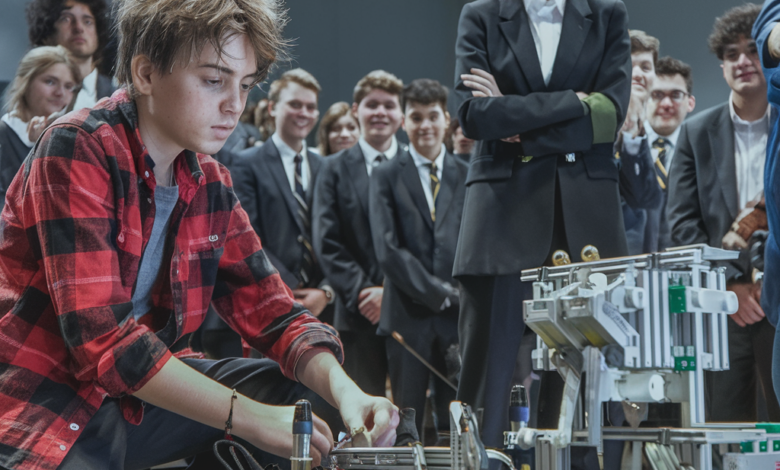

But the real test came later. Richardson led the class into the experimental lab, where the same research engine sat. “This machine has failed diagnostics for months,” she said. “If Mr. Granger can repair it in ten minutes, I will admit I was wrong.” The room went still. Elliot pulled on work gloves, circled the engine, and crouched by the pump housing. After a pause, he said, “It’s cavitation. The aluminum housing expands faster than the steel gears. The clearance tightens, oil flow chokes, bubbles collapse, and the pump eats itself.” He added a small amount of molybdenum disulfide to the system, then started the engine.

It hummed to life—steady, smooth, stable. Gasps filled the room, followed by applause. Richardson extended her hand. “I was wrong,” she said publicly. “Entirely.”

From then on, things changed. Students sought him out. Richardson began calling him “Elliot,” not “Mr. Granger.” The once-dismissed boy was now trusted, his insights respected. He diagnosed the engine’s deeper flaw—an inferior replacement sleeve installed during a sloppy rebuild—and proposed a full fix with new alloys and adjusted tolerances. When Richardson asked how he knew, Elliot simply said, “Machines tell you, if you listen.”

By semester’s end, Elliot had built his own small engine out of salvaged parts. He placed it on the desk, turned the crank, and let it hum. “This one isn’t designed to push,” he said quietly. “It’s designed to wait.”

Professor Richardson, who had once dismissed him at the door, filed an official recommendation: Elliot Granger should be granted mentorship and independent project access. He reminds us that machines aren’t puzzles to solve, but voices waiting to be heard.

Elliot didn’t need applause. He needed only the hum of an engine running true, proof that listening was enough.

Years later, students would still talk about him—not as a prodigy, not as a charity case, but as the boy who taught them to hear again.